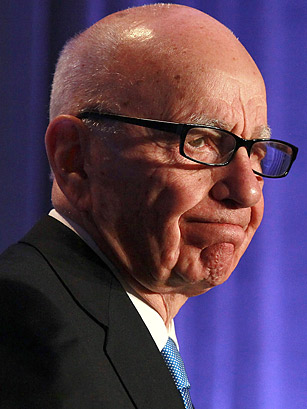

It wasn't until the media tycoon's powers were weakened — by a phone-hacking scandal that shuttered his 168-year-old British tabloid News of the World — that the true extent of those powers were revealed. The shock waves reverberated across a business empire spanning four continents and ranging from the high-minded (the Wall Street Journal, the Times of London) to the defiantly populist (Fox News, the New York Post, British tabloid the Sun). It also rattled Rupert Murdoch's network of friends in high places, not least Prime Minister David Cameron, whose director of communications, former News of the World editor Andy Coulson, resigned and was later arrested on suspicion of corrupt payments to police. When Murdoch, 80, was grilled by a committee of British parliamentarians — and hit with a foam pie by a protester — he looked like a spent force. But he weathered the fractious annual general meeting of his U.S.-based News Corp. and, ignoring investors' calls to reduce his hands-on role, added to his load by taking on the chairmanship of News Corp.'s Australian arm. He appears determined to stop making news and keep shaping it. For now, he's succeeding.